Virginia Crawford is a long-time teaching artist with the Maryland State Arts Council’s Artists-in-Education program. She earned her BFA from Emerson College, Boston, and her Master of Letters from the University of St. Andrews, Scotland.

Q: You’ve previously published another poetry book Touch; did you learn anything from that experience that you applied to this project? Is there anything you learned through the writing process of questions for water?

A: Yes, I can think of at least 2 similarities. First, keep putting the work out there so its chance of finding a home increases. Second, Touch also did not have a publicist beyond myself, so I had to create my own “book tour.” Thankfully I had many poet-friends who ran reading series, so reaching out and requesting a reading was pretty easy. Over several months I managed to present my book in most of the states from Virginia to Vermont. In places where I didn’t already know someone, I did some research on reading series in that area and emailed the organizers. Several agreed. Beyond these things, I hope to have the extreme joy of reading to people in person and signing books for them as I did with Touch. I really, really love giving readings — particularly making eye contact with the audience and watching their reactions. That interaction, their listening, and their facial responses — I may be reading poems out loud, but I’m actually reading their faces. That is one of the most satisfying things I’ve experienced. Being heard and understood. Sometimes people share their thoughts, their appreciation individually — that deep sharing, a kind of intimacy with strangers, few things are that wonderful. What did I learn through writing questions for water? Perhaps that collaboration is extremely helpful and productive. I would not have written the title poem if I hadn’t been invited to participate in the writer/artist program at the Hamilton Gallery. The poems would not be as strong if I didn’t have a small but awesome critique group. They were significant in helping me revise and edit and also create the sections and order the poems. That help is invaluable.

Q: Themes of parenthood, identity, and social issues such as gun violence and immigration are prevalent in the poetry; what inspired you to write about these subject matters?

A: Everything I write about is important to me. I’ve long worried about gun violence, particularly in schools, but when you already fear sending your kids to school every day because of the potential for unpredictable and horrific violence, and then your child recounts an actual lockdown including what he was thinking in those moments…that’s pretty intense, traumatic and sad on many levels. That nugget of intensity or shared human characteristic, like the desire to feel safe, successful poems grow out of that. Sometimes I have experiences or feelings that I just don’t know how to process, so I put them in a poem. Other human beings, being more similar than not, can relate or have had similar feelings. Most of my poems come from my life experiences and the experiences of others I see around me as well as those in the news. There’s a lot of poverty in America; there are millions of hungry and homeless people living in the wealthiest country on the planet. That’s injustice. I don’t have the resources to resolve that injustice, but I can show people’s suffering, that they are humans deserving of respect and assistance. Someone who never considered poverty and all the suffering that comes with it might hear or read my poems, and they might think about it. They might be kinder to the next person who asks them for help; they might make a donation to a helping organization; they might start keeping snacks in their cars to give to people begging at streetlights. Anything. Some people will think this is ridiculous and/or naive; what percentage of the population even reads poetry let alone becomes kinder or more generous as a result? Don’t answer that. But I want to raise awareness about people’s suffering; I want to provide a way for people to consider their beliefs and habits and ask themselves how they can be more helpful to humanity. Poor and homeless people are invisible to many Americans. Many Americans don’t want to listen to their struggles and help them. I have had the opportunity to speak to people many times. If you see suffering or injustices, you should do what you can to help. I can’t buy an apartment block for the homeless people of Baltimore, but I can show them and their suffering in my poems; I can read those poems to hundreds, hopefully thousands of people. Outside of looking people in the eye with dignity and giving a few dollars or food when I can, I can raise awareness and encourage others to do what they can by showing their experiences in my poems.

Q: What are the advantages of discussing these issues in poetry?

A: Well, poetry is what I write; it’s the way I share what’s important to me with the world. If I feel that intensity, that twitch that insists on being put down on paper, I write a poem about it. There’s a long international history of poems addressing social justice issues. I first read poems like these in college, in a class Martín Espada taught. Before that I didn’t know much, if anything, about poetry that discussed social justice issues. That class really opened my eyes to that. I don’t think I would have written many of the poems in questions for water if I hadn’t taken that class. Advantages…some people read and discuss poetry, and that can start a conversation about the issues in those poems. Poetry is still taught in high schools and colleges. Once young people are aware of issues happening around the world, some might become interested and go on to a career related to one of them. Poetry also provides an opportunity to learn empathy and experience sympathy; personally, it also provides an outlet when I am moved or outraged and unable to do anything concrete to change a situation. I can write about it and hopefully alert others to the issue. The likelihood of solving or resolving an issue increases as more and more people become aware of it. I hope my poems can be at least a small step in that direction.

Q: You said you selected the title questions for water in response to a painting; what about the painting inspired you to title your book this and what is the significance of this title to your book as a whole?

A: I wrote the title poem, questions for water, in response to a piece of visual art — part of a project at a gallery. Visual artists and writers paired up, and the writers wrote in response to or in relationship with the art. The piece I chose was a mixed media painting that included paper and a segment of barbed wire. Yes, literal pointy rusted barbed wire. The painted surface was a gorgeous mixture of blue and green representing an ocean, the paper shapes I interpreted as a lighthouse, a single person in a rowboat, and torn paper as mountains. The barbed wire was attached across the bottom of the painting, and I interpreted that as the challenges, all the difficulties that must be overcome to immigrate to a new country. One of my grandfathers came from Italy when he was 3, and I’d always been curious about that and wanted to write about it. So, here was a work that presented elements of that immigration experience. There’s also the concept of journey which relates to so many of the things I write about–the journey of marriage, parenthood, my grandfather’s and others’ journey to becoming Americans — all kinds of “journeys.” It’s been horrific to see the treatment people have received in the last few years when they try to come here and build better lives for themselves and their families. Enormous amounts of needless suffering and trauma inflicted on people out of hatred and fear. In a previous job I had the opportunity to meet and talk with many immigrants, many from Russia, and several from different countries in Africa. In an even earlier job, I worked with many immigrants from Nigeria. All of these threads or journeys came together in my mind with this image of a blue-green ocean and barbed wire. I wrote a long poem incorporating elements of my family’s history, histories of those I met through my work, and the atrocities that appear too frequently in the news. It’s the longest poem I’ve ever written, but more importantly, it touches many of the subjects of other poems in the book, so it felt like a good representation of the whole book. And the idea of asking water questions, I wish I really could do that. And perceive the answers. I’ve always been fascinated by water: how it can change and change and change and still be water, how it both connects and divides the lands in it, how it moves in varied ways, how it looks on individual blades of grass, how it comes from the sky in several forms, how it’s different colors in different places, how it supports life living within it and out of it, how refreshing it feels going down on a hot day, how you can soak in it, swim in it, sail on it…water is awesome! I really wish it could answer my questions. Being imperative to life and covering most of the earth, I imagine water has quite a lot of wisdom. Consider the things it’s seen…

Q: Why did you choose not to use punctuation and capitalization in this book?

A: The short answer is because their function is to separate things. Many of my poems are about separation or loss or yearning, a desire for togetherness. Life is not tidy. People and relationships are not tidy. Everything is temporary and using standard punctuation and capitalization can provide an artificial sense of clarity, of certainty, and predictability. Punctuation allows the illusion that things are clearly separate from each other. Nothing in life is clearly separate from anything else. All our experiences come with us into the future. People’s lives are meshed with other people’s lives even if they live alone and don’t talk to anyone else for a day or for years. Part of the title poem comes to mind: if there was a door / we could open inside our minds or / here on our chests / what country would we see inside // swimming lanes / are only divided on the surface. People can be excessive in their identification with their country. That often creates division–“us vs them,” and the idea that one group or nationality is in some way better or more valuable than another. Which simply is not true. Open anyone’s skull and you’ll see a brain, or their chest and you’ll see a heart and lungs. This artificial division, this delusion, is incredibly superficial and detrimental. Same idea with swimming lanes. Those dividers do not literally divide the water in the pool. They only provide the illusion of division. Not using punctuation or capitalization makes all the words equal to each other. They’re each a drop of water in the ocean–all equal to each other. The way I wish each human being was treated with equal respect. You could even say my rejection of standard punctuation and capitalization is a way of rejecting society’s social hierarchy.

Q: The book is split into four parts; what is your purpose in doing this?

A: The book is split into 4 parts because the title poem is a long poem and also to provide a sense of movement through time. A long poem is awkward thrown in among shorter ones. I didn’t want it to be the first poem because it might intimidate people. Poetry readership is small enough! You don’t want to give anyone a reason to immediately put your book down once they’ve picked it up! And it would have felt tacked on if it was the last poem. The title poem is its own world. It deserves its own space in general but making it one section lets people know specifically this is one thing. The first section of the book is more recent poems. I wanted people to be able to connect with (relatively) current events as a way into the book. The last two sections tell a lot of back story, you could say; the reader gets to see how I came to the poems in the first section and also suggests the process of aging, the passage of time.

Q: Do you have a favorite poem within questions for water?

A: A favorite? That’s like asking a mother which is her favorite child! That’s a hard question. There are so many precious ones. I’ll go with the title poem because it weaves parts of my life with those of others around the world. It also speaks to several forms of injustices such as poverty, violence, and abuse of people trying to become Americans.

Q: In what ways, if any, is questions for water different from other works of poetry you’ve created?

A: questions for water–the individual poem–is different from other poems in several ways. First, it’s an ekphrastic poem–a poem written in response to or relationship with, in this case, visual art. I have done that before, but it had been quite a while. Second, it uses a lot of repetition which I don’t often use. The repetition both provides something familiar for the reader, and it acts as a transition into different subjects. The poem makes many jumps in terms of its subjects, and the repetition is the rope that helps the reader into them. It connects all of these different but intersecting subjects. Third, it’s the longest poem I’ve ever written. 1-3 pages is typical for me. I think questions for water is 11 pages.

In terms of the whole book being different from my first, the most significant difference is the number of pages. Touch was about a third of the size of questions for water, so there wasn’t room to create sections. It had to move in one line from start to finish. There were several poems on social justice issues but not as many. There were more poems focused on my own experiences.

The publishers are also very different. I had little contact with my first publisher. I felt a bit like a product on their very impersonal assembly line. I have much more contact with Apprentice House. I can attend update meetings on Zoom almost every two weeks to hear where we are in the process and share my preferences. They ask for my input whereas my first publisher felt very “cookie cutter.”

Q: What do you hope readers take away or learn from your poetry?

A: That there is beauty and strength in human connectedness, and as hard as it is sometimes, we need to trust that. That humans are more interconnected than many want to admit. That there are serious, unjust things hurting human beings that need to change before you get to the end of this sentence. That humans can join together to fix those things and show respect for each other for no other reason than the fact that they are human. That all humans need to respect all humans.

Q: What advice would you give to young people who want to publish their work?

A:

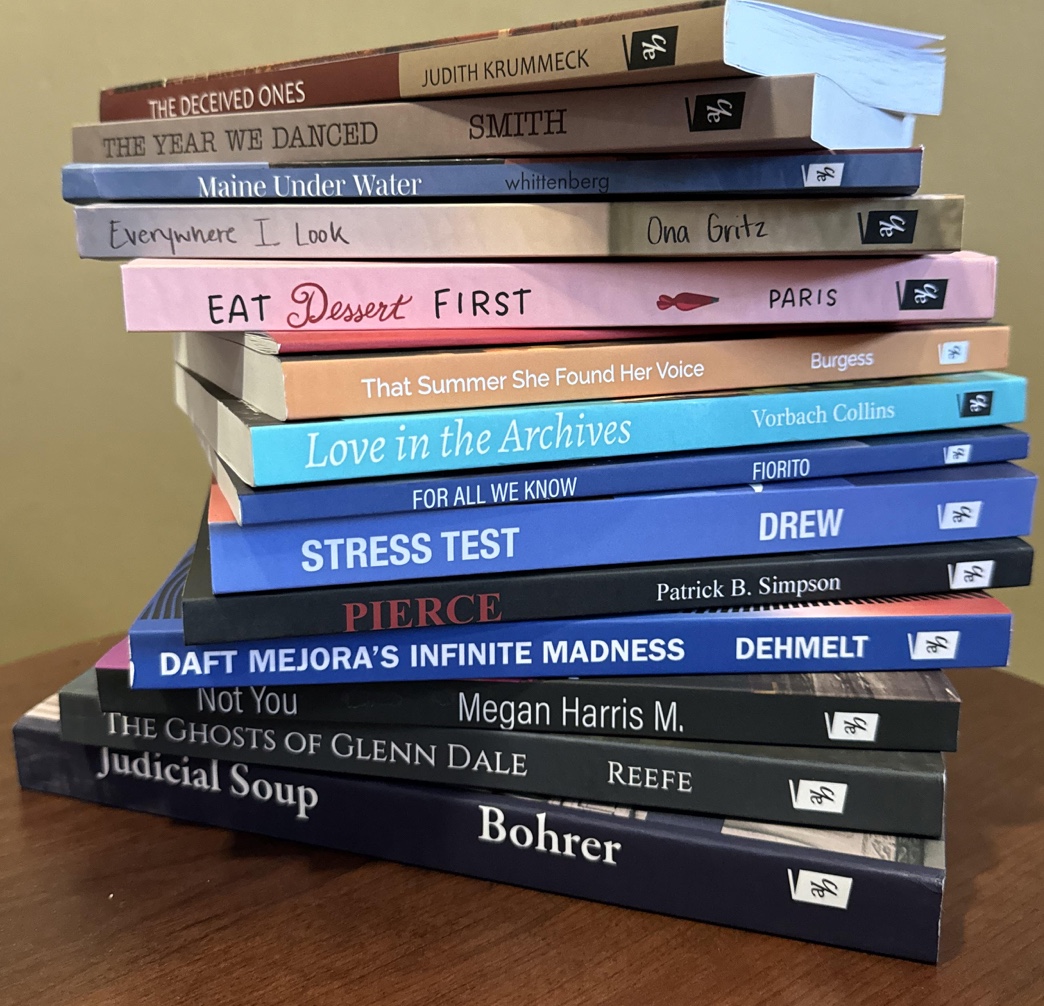

#1. Read, read, and read. Read people who are like you and people who are unlike you. You do not have to LIKE everything you read. But each book you read, gives you more information about what a book can be, and in some cases, what you DON’T want your book to be.

#2. Don’t be afraid to be influenced by what you read. You will be influenced. And that is a good thing. Unless you’re specifically trying to mimic another writer, you’re not suddenly going to lose your own voice. Think of it more like looking into another writer’s toolbox. Some things you appreciate in them might be useful to you. Other things will not. Just because you have a hammer in your toolbox doesn’t mean you have to use it. Reading widely will expand your vision of what poetry can be and give you options you may not have considered if you had not read a particular author.

#3. Attend readings and festivals in person when it’s safe and online until then. Listening is similar to reading, but things go by much more quickly and you usually can’t re-read a piece. I often take notes at readings. If I hear something that knocks my socks off, I’ll write it down in quotation marks. Often reading or listening to someone else will spark my own ideas, so I jot those down too.

#4. Make an effort to develop friendships with other writers. Not only will they understand issues related to being a writer, but they will know things you don’t and vice versa. You might introduce each other to other writers, festivals, contests, etc., you might otherwise never have known of. These friendships can be wonderfully supportive and mutually beneficial but beware of those who will ONLY talk about their own work, their own process, success, failure. Just like friendships in other parts of your life, mutual support and kindness are required.

#5. Establish a critique group and meet regularly. It helps you keep a certain level of focus – so you will have a revision or something new to share with the group. Allow others to say what they perceive and like and don’t like without interrupting to explain what you meant. Listen to how people perceive what you’ve written. This will tell you a lot including if you communicated what you intended to or not. Often listening to others’ comments will show you what you need to revise and what worked well. Sometimes people will see something completely different from what you intended in your poem. It’s not always important to “correct” them. Listen to their perception. It might give you ideas about revision, and every once in a while, you might find their perception more interesting than what you intended. So be receptive to feedback. But remember that it’s up to you to accept or reject others’ suggestions. Take what’s helpful and leave the rest.

#6. When you sit down to write, put the internal critic aside for a while. Let them know you’ll be back for them later. But when you start or want to add to a piece, you have to listen to that deep voice in yourself. It’s difficult to describe. That part of you that perks up or gets excited or interested in writing about something, but also the quiet, contemplative voice. So much of writing is listening to those internal voices. You might need to experiment to find ways to let those deep parts speak to you. Some might need silence, some need music playing, some find writing easier in particular environments and more difficult in others. Find what helps your voice speak up. But don’t let it bully you or create a massive ritual that uses up all the time you have and actually prevents you from writing. Find what’s best for you, but don’t allow it to become so elaborate or extreme that it prevents you from writing. Flexibility and adaptability are important too.

#7. Look for places where your work might fit – Submittable and listings in magazines/websites like Poets and Writers can be great resources. Pay attention to what editors are asking for. If they are asking for poems about siblings, for example, don’t send poems about nature or roller coasters. That might seem obvious but paying special attention to what editors are asking for will increase your chances of acceptance. Not all publications/websites are appropriate for all writers. Send your work out and don’t take it personally if/when it’s rejected, or you get no response at all. That’s part of writing. If you eventually want to publish books, it helps to get individual poems/stories/pieces out there in the world. Publishers like seeing that your work has already been accepted elsewhere-another editor has already given your work a seal of approval.

#8. Be prepared for it to take a while to have a book published. I don’t mean months or years, but sometimes decades. Yes, there are many options for self-publishing which could be very quick, but I never wanted to go that route. Different writers will value different things, so investigate the options and find what feels right for you.

#9. Know that it gets easier…maybe more familiar is more accurate. The longer you write and submit your work to editors, the more experience you accumulate. Very often experience leads to familiarity, and familiarity usually increases comfort levels.

#10. Writing is work and can be challenging, but don’t forget to enjoy it. I love that feeling of satisfaction I have when I can feel a poem is finished. That and reading to people and watching reactions appear on their faces is wonderfully satisfying to me.